In the summer of 2018, I returned to my native country of Luxembourg for the first time since I was five years old. It was the third in a series of journeys I’ve undertaken during the past few years to the significant places of my childhood — New Mexico, Oregon and Luxembourg. I also hoped that immersion would give me back my ability to speak and understand my native language — Luxembourgish, which is indeed an actual language (not just a dialect). This is the story of that journey.

“Moien” technically means “good morning” in Luxembourgish, but it’s also used as an all-purpose casual greeting, much like “hi!” at any time of day. This was the sign that greeted me at the train station in Luxembourg City as I arrived.

Just a bit of background: Luxembourg covers an area of approximately 998 square miles. By comparison, the County of Los Angeles is over 4700 square miles. A tiny country, but very diverse and with much to explore, both in its own right and in terms of my own personal history. It’s also the second richest country in the world with an average GDP per capita of $79,593,91. Damn those socialists for taking everyone’s money… oh, wait…

At any rate, as the train pulled into the station, I felt that blend of nervousness and excitement that comes with seeing an old crush again for the first time since childhood. Would Luxembourg like and accept me? Would my fellow Luxembourgers recognize me as one of them or would I be an outsider because of my years… a whole lifetime… away? I don’t have a “home” in the US in the way that most people use the term, and I realized suddenly how much I was counting on Luxembourg to feel like one. My last hope for home, even if it’s almost 6000 miles away.

Luxembourg City. My native soil. I was born here, I keep thinking over and over again. A small thing to someone else, perhaps, who has a hometown and a family and roots, but to someone without these things, an emotionally seismic experience. I was born here. This is my country. To be rejected by it for my years spent in the US feels as if it would be too painful to bear. The emotional stakes are higher than I had quite realized.

The Grund District in Luxembourg City. If I were ever going to live in a city, this is where I’d want to live. You can’t see her, but on the right hand side, there is a woman sitting on her balcony overlooking the river, writing….

My first stop was the Cathedral of Notre Dame, the “national” cathedral of Luxembourg. My grandfather was the (or a, not sure which) Master Carpenter for the country (or city, not sure which) of Luxembourg. He supervised the building of the roof on the cathedral. I grew up hearing my mother tell the story of her and my grandmother climbing up the scaffolding to pound in nails when the project was behind schedule. The scraps left over from the roof became our family dining room table, as well as a few other things, including a candle holder that I still have.

I spent a little time annoying strangers by explaining this to them. They were not impressed, but I sure was. 🙂

The Chapelle Saint-Quirin is a tiny church literally carved into the side of a cliff. It’s nestled in the Pétrusse Valley, a park that runs through Luxembourg City along the old fortified walls. It’s long been considered a place of miracles.

A dinner of kniddelen (every letter is pronounced, including the k), a traditional Luxembourgish dish that my grandmother used to make for me when I was a little girl. They have no nutritional value whatsoever, just flour and water dumplings with brown butter and bacon. But oh, so good! The ultimate comfort food, really. Luxembourg food is basically French flavor with German portions — yum!

On the walk to the next stop, the first of many castles — Beaufort Castle. At the cathedral in the village, a choir was practicing and I stopped to listen. Maybe it’s because they were singing in Luxembourgish, maybe because I was exhausted and my defenses were down, but I was suddenly overwhelmed with memories of my mother.

I remembered that she’d always said that someday she and I would go to Luxembourg together and she would show me the country of my birth. We are estranged and have been for over a decade– her choice, not mine — so that trip will never happen, and I am achingly sad for what is lost for both of us. This journey should have been ours, not just mine.

It’s been since the Camino that I walked this far in a single day… fortunately, there were an abundance of streams to soak my feet in.

Next stop, Ettelbruck, where my mother and her side of the family are from. I probably have relatives here – one man I met walking his dogs asked me their last name — Bodeving — and recognized it right away.

My Luxembourgish is getting rapidly better as my ear adjusts to the rhythms and cadence again. Random words come back to me at odd times — folding clothes into my pack in the morning, I remember the word for potato. On the bus, “scissors” comes back to me, along with the full syntax — I cut, you cut, they cut, I have cut, etc. It’s like remembering fragments of a dream from a long time ago.

It’s an odd experience for me to hear strangers speaking Luxembourgish. Since I only spoke it at home in the US, I’ve never heard anyone speak it outside of family. It almost feels like an intrusion — like coming home and finding someone sleeping in your bed.

Spaghetti ice cream turns out to be a Big Thing in Luxembourg. At cocktail hour, I noticed Luxembourgers gathering in coffee shops and bars, ordering not drinks, but elaborate ice cream sundaes in various configurations. I thought it odd until I ordered one and discovered it was laced with alcohol…

A Highland cow looks out over Diekirch, where my mother’s side of the family still lives. I didn’t look them up (my family, not the cows), but it was nice to finally see the place I heard about so often while growing up.

One of the things I wanted most to see was Fautefiels. a tiny chapel carved into a rock. It was used as a secret place of worship during the French Revolution, when religious activities were prohibited.

It was so secret, in fact, that it was difficult to find. I asked a couple of the villagers for directions, and either my Luxembourgish was not functioning or they truly had never heard of it.

Coming back up the trail after seeing Faltenfields I suddenly remember the Luxembourgish word for lucky.

A night of camping, nestled alongside a river in the Luxembourgish Ardennes.

Vianden Castle is perhaps the best known tourist destination in Luxembourg. There are lots of photos of it online, but my favorite of the my visit was this one. The juxtaposition of the modern and the ancient is a perfect representation of Luxembourg.

One thing that struck me about Vianden Castle was how familiar a lot of the interiors looked.

Up until my mother was 16, her side of the family was wealthy and prominent. I doubt they lived in a castle, but certainly they had money. My grandmother married a working man of lower social class who had no idea how to handle the family fortune and he lost it all on bad business decisions. They kept the furnishings, and brought them to America with them when they emigrated in the early 70s.

During my early childhood, we were dirt poor in America — we lived in a trailer park in New Mexico and my parents were on food stamps while both of my parents became the first in their families to graduate from college. But we always had this incredible furniture that my mother brought over from Luxembourg — much like the furniture in these photos — along with crystal and porcelain and art that, again, looks much like the stuff in Vianden.

My mother never forgot her fall from grace. Though she became a teacher and wife of a working man in a tiny town in southern Oregon, thus repeating her mother’s choice, she ruled over that small town like a queen, hosting gracious and opulent dinner parties for the mayor and other notables, and creating her own castle in the woods as best as she could.

It was a weird juxtaposition — being so poor and yet living surrounded by that kind of opulence. It still defines me — somewhere between the “white trash” of my early years and the wealth and privilege of my heritage, I try to find a home.

In a field of sunflowers, only one was in full bloom. I talked with her for a little bit. She was an old soul.

Church bells… on my way up to the castle in Esch-Sur-Sure, I heard another choir singing, so of course, I followed the sound to the local church, where a baptism was in progress.

A handful of family members baptizing a new baby in what was certainly their village church. A beautiful simple ritual that welcomed a new member into the community.

And I thought about how the choir came on a Saturday morning to sing the little one into the tribe, even though they are almost certainly not paid. And how it really does take a village. And how we’ve lost so much of that in the US.

Being a minimalist and, more practically, constrained by needing to carry for the rest of the trip anything that I bought, I hadn’t bought anything other than food till that point. But then I saw this simple necklace in an antique store.

It was a magical little place, at the end of a tiny narrow little sidewalk, owned by a kind man who not only waived away the price and settled for a handful of change, but also gave me great directions to the trail I was searching for and… and who spoke the kind of Luxembourgish I remember from growing up in terms of cadence and dialect. It was with him that I finally had my first truly fluent conversation, complete with jokes and laughter, and didn’t have to use my pre-prepared apology, “I’m sorry my Luxembourgish isn’t as good anymore…”

I discovered that the best way to get my Luxembourgish back was to start talking, and then talk as fast as I could without thinking of the next word, and letting my sense memory kick in, rather than trying to “remember” consciously. It’s essentially the Evil Knievel method — go really fast and you’re more like to get over the hurdle and not plummet to your linguistic death.

I like that the necklace is old, too. Choosing something old from the country of my birth feels better than a new thing would.

The next part of the walk took me into the Moselle Region, which is known for its wines on both the Luxembourgish and German sides of the Moselle River. Acres and acres of grape vines cover the hillsides on both sides of the river.

The ferry in Grevenmacher that crosses the Moselle River between Luxembourg and Germany. You can perhaps see that there’s a Luxembourgish flag on one side and a German flag on the other.

Being on the Luxembourg-German border has affected me more deeply than I anticipated.

Like many whose family lived in Europe during the Second World War, I was brought up to hate all things German. I was well into my school years before I realized that the word “German” does not automatically include a four-letter curse word before it.

Crossing to the German side, I confess that I was uncomfortable in Germany, even though I was just a stone’s throw from Luxembourg and certainly no one here today had anything to do with what happened during the war.

My grandparents were young parents during the Second World War. They tell stories of helping the Resistance. My grandmother tells of twice being taken away to be interrogated by the Gestapo and leaving my mother, then only a few years old, with a neighbor in case my grandmother was sent to the camps for aiding the Resistance.

My favorite is a story about a wealthy Jewish man who paid my grandfather 100 gold pieces to make him a set of hollow wooden clothes hangers to hide his gold in when he fled to the US. All were spent, except one which was melted into a ring with our family initial on it. I still have that ring today.

A heroic and romantic story, but I’m not convinced it’s the whole story. I’ve also seen travel documents in my grandfather’s name with a swastika on them, and I know that my family’s prestige and fortune survived the war intact, and I know enough to know that living in occupied Luxembourg meant a certain amount of moral flexibility just to get by. I wonder about the guilt and shame, particularly as I struggle with my own complicity in what’s happening in the US right now. I think my family, like every Luxembourgish family that survived the war has ghosts and secrets.

And I worry that someday someone will write just this about America. That people will struggle to forgive for what we’re doing — what we might do — to the world. And because of this, I struggle to forgive, hoping that we might be forgiven when the time comes, if we fail to heed the lessons of Germany’s history

But today, the border between Luxembourg and Germany is peaceful. I watch tourists, bike riders, families cross on the ferry, taking photos and smiling.

I don’t often think about peace, but it’s on my mind today. I think about how it was, how this land has been through two modern World Wars and many others before that. I think about how hard both sides have worked to create the European Union, formed just a little over a decade after the end of WWII. I think about how easily Americans go to war, and how the Europeans resist because they know, in a way that we don’t, not really, the cost of war and the work required to bring a culture back from it. We are geographically isolated in the US. Europe does not have the luxury of insulting its neighbors. Europe understands the costs of war and the blessings of peace in a way that we don’t seem to.

It’s the unexpected parts of an adventure that make it more than a vacation. A moment when you turn the corner and find something you hadn’t considered, and the world as you know it shifts a little.

It took me a minute or two, as I looked at it, to realize that this monument that I stood in front of was not in Luxembourg, but in Germany, with the WWII German soldiers from this village who died memorialized on the wall inside.

My world spun a little as my mind slipped and slid on this, standing here in a little town in Germany within sight of the Luxembourgish border. A memorial to soldiers who fought against Luxembourg, against the Allies. For Hitler. It honestly hadn’t occurred to me until that moment that, of course, there would be memorials to Nazi soldiers in Germany in the same way that there are memorials to fallen Civil War soldiers in the American South.

I know not everyone who served in the army of the Third Reich agreed with Hitler. I know firsthand from what’s going on in America right now how hard it is to stand up against injustice, even when you know it’s wrong. I know every name on that wall is someone’s son or husband or father, someone who loved and laughed and was mourned by someone.

I know not every soldier supported Hitler. But I also know that many did. I still can’t wrap my mind around how I feel about this, as a Luxembourger, an American, a human being.

Just south, still on the border, is Schengen, known for being where the Schengen Agreement was signed on a boat in the middle of the Moselle River, between Luxembourg and Germany.

This is the actual Schengen Agreement that opened the borders between the original five countries — Luxembourg, Belgium, the Netherlands, France and Germany, and subsequently, many more.

Spending this week on the Luxembourgish/German border moved me deeply in ways that I didn’t expect. I think it was seeing two countries living so (seemingly, at least) effortlessly and peacefully side by side after having been at war so many times in the past. And thinking about the forgiveness and the empathy and the commitment to a better way that it took to make this peaceful border happen.

In a small church in Grevenmacher, a box containing head coverings for women to wear in church. Luxembourg is a very Catholic country, and even though, like the rest of the Western world, it is largely secular at this point, the Catholic influence is still everywhere in the culture.

Even though I have serious issues with organized religion and am a passionate supporter of the separation of church and state, I really love what having a national religion does for the ambiance of a culture. When it’s used with a gentle touch, as in Luxembourg, it enfolds everything in a soft veil of spirituality and grace.

After the Moselle region, I headed south to Esch-sur-Alzette, the second largest city in Luxembourg. This part of the country is known as the “Red Rock Region” because of the way that the iron ore used in the old steel factories turns the ground red.

Like most other places where labor gets a fair wage, Luxembourg’s steel industry hit the skids awhile back. The region did a bit of mourning about it, but then they did something that takes my breath away with its beauty…

There is an old steel mill outside of the city. They could have torn it down, or let it decay. But instead, they turned it into a university. And a library. And a community gathering place. All the while preserving large sections of the mill as a testament to what was.

The architecture and design are innovative and stunning, but more than that, what struck me was the hopefulness, the resourcefulness, the ingenuity. In America, the Rust Belt is busy whining about lost jobs and voting for Trump’s false promises to bring them back. In Luxembourg, they’re turning closed mills into places of learning and community (not shopping malls).

I didn’t expect to be inspired by my visit to this part of the country, but it’s been one of the most inspirational parts of my journey.

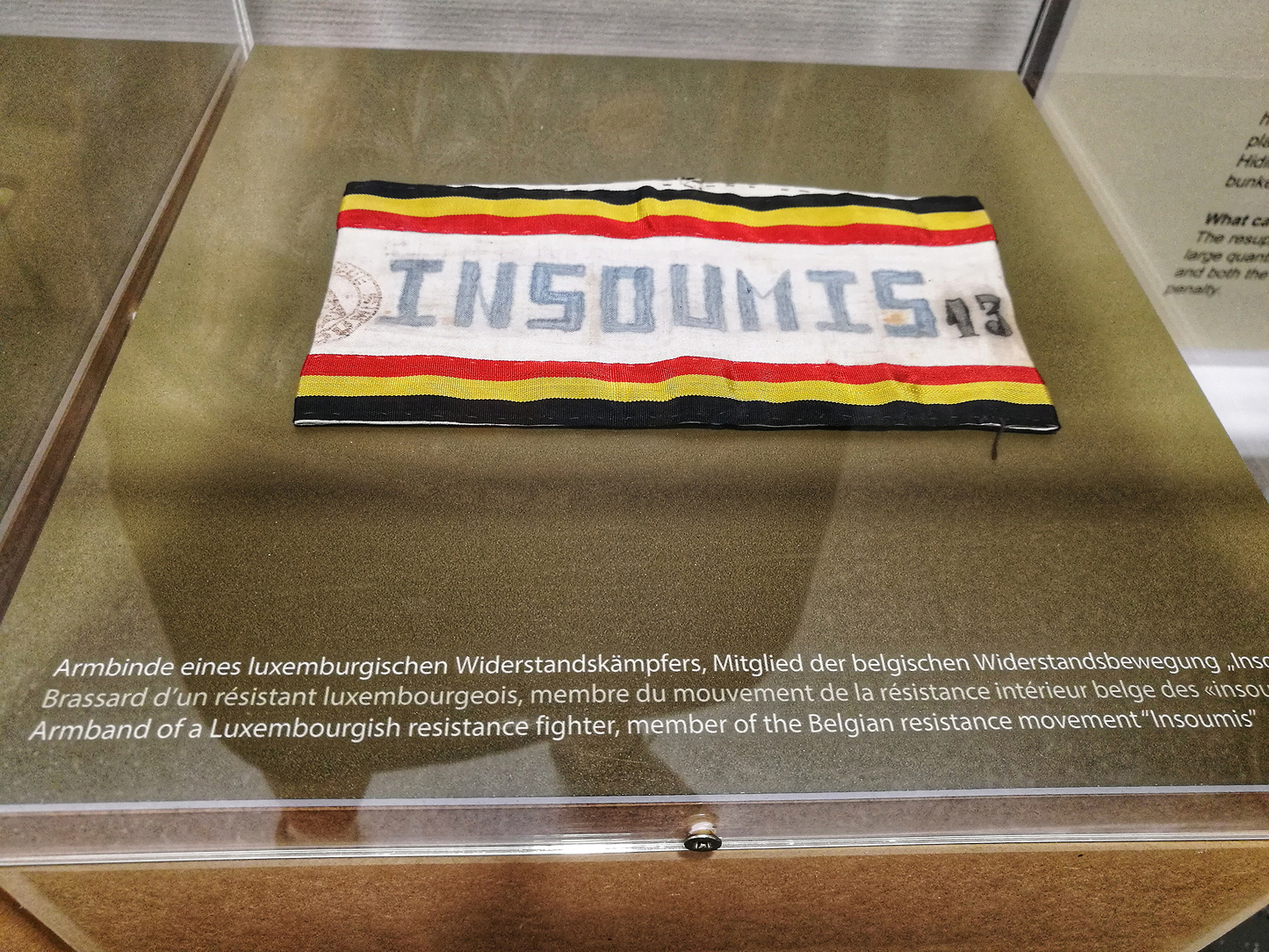

In Esch-sur-Alzette, I went to the museum documenting the Luxembourgish resistance against the Nazis. As you might imagine, it was both inspiring and difficult. This is an armband worn by Luxembourgish Resistance members.

It was inspiring to see how Luxembourg resisted, of course. And to think/hope that maybe some of the stories I grew up hearing about my grandparents working with the American resistance are true. Difficult because of being reminded that many Luxembourgers bought into the Nazis’ anti-Semitism and not only went along with things, but were active supporters. And also because knowing that my grandparents survived the war with their property and fortunes intact makes me uncomfortably suspicious of a certain amount of appeasement of the Nazis on their part.

I think it’s a miracle that, tiny as it is, Luxembourg has retained its national and cultural identity as distinct from its larger, more powerful and more warlike neighbors. It’s like the plucky kid in school who somehow manages to resist all the peer pressure and stays true to him/herself

After “industrial” Esch-Sur Alzette, I was happy to get back to the woods. This is in the lovely village of Consdorf.

I found that Luxembourg is a walker’s dream. Almost every village has its own circular/looped walking trails that wind through the surrounding countryside.

I met royalty today. The real kind. This is Maria, the well-named Elder Tree of Luxembourg. As you can see, she is very old and very wise. She has a place inside her where people come to light candles. I can only imagine how many people have come for hundreds of years with their hopes and dreams, joys and sorrows.

Maria the Elder has stood through the tumultuous events of Luxembourg’s history. She now, rightfully so, has a lot of help from humans, as you can see by the many support ropes that help keep her branches strong.

I cannot even begin to tell you how awed and humbled I was in her presence. As my offering to her, I cleaned up the area around her trunk — there wasn’t much litter, but there were a few things — and offered the rest of my bread to the beings who call her body home.

A couple of nights in an historic chateau. The owner restores WWII vehicles and took me for a ride through the Luxembourgish countryside in this WWII Jeep with Finn, the dog (while drinking a bottle of beer… such are adventures sometimes…).

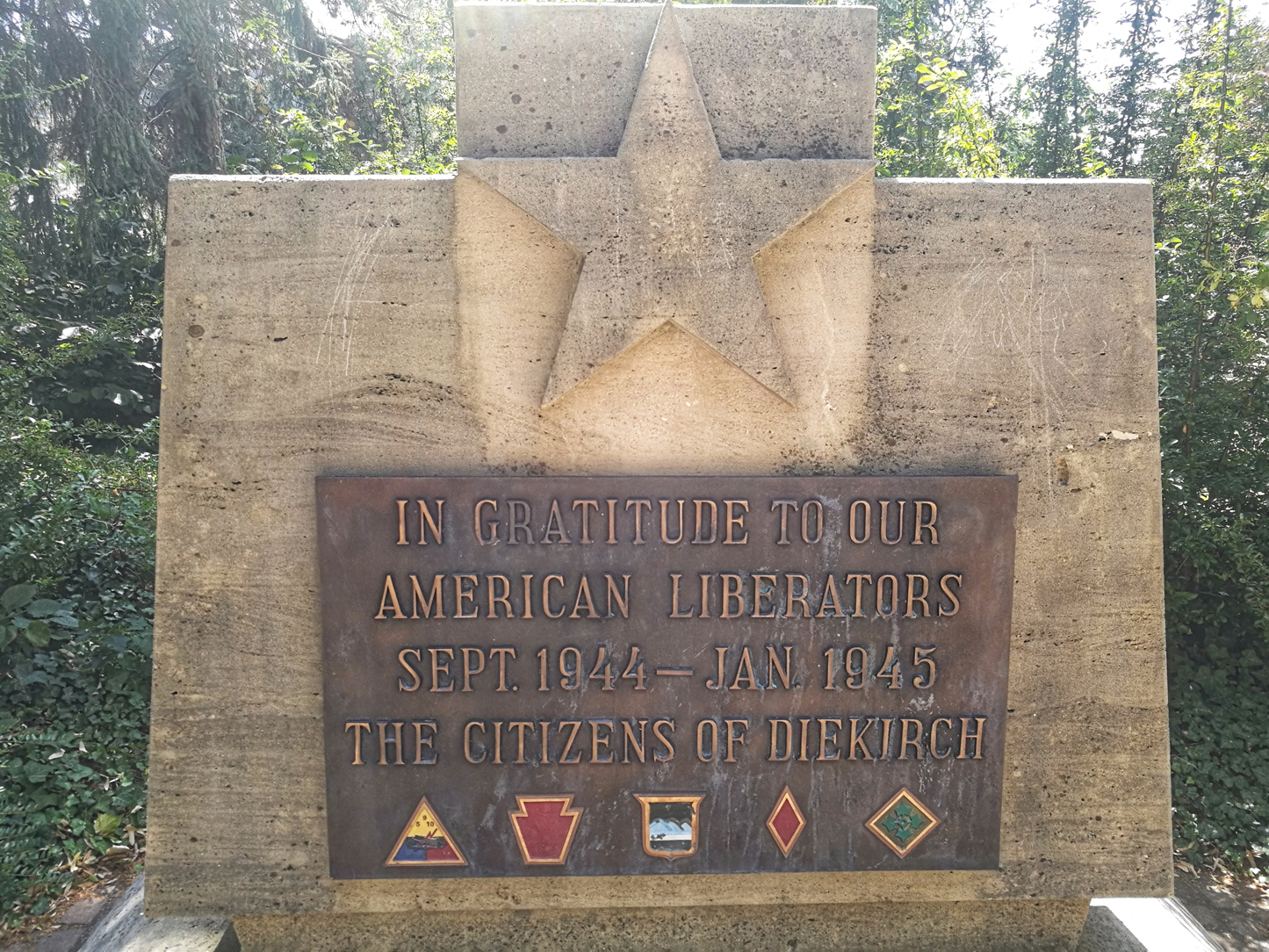

Remember when we were the good guys?

These memorials of thanks to US soldiers are ubiquitous in Luxembourg. I spoke to so many people who were so confused by what’s happening in America right now. Some of them wanted me to give them assurances that things would be okay, which I couldn’t do, of course. Some of them just wanted an explanation. Some of them assumed that the news must be distorting how bad it was — they simply couldn’t bring themselves to believe that the same American they knew from World War II could be doing such terrible things now. As on the Camino, I soon learned how to be fluent in my apologies for what our country is doing in the world. It sucked. And it broke my heart.

In the north of the country, tucked away on the top of a mountain, is the monastery at Clervaux. The monks at Clervaux are famous for their Gregorian chants. I fulfilled a life’s desire in listening to the chanting of the Hours.

The walking highlight of the adventure was the Mullerthal Trail, which winds through Luxembourg’s “Little Switzerland” region, one of the most beautiful places I’ve ever been. I felt I was walking through a fairy tale.

Crystal clear water spilling into a small pool took my breath away with its beauty. I didn’t think it could get more lovely, but I kept walking and found where the water was coming from…

Above the waterfall was a fairy pool. I’ve never seen water this clear in my life. I drank some of it and I swear it tasted like the Fountain of Youth.

I don’t know who made it or why, but it felt like a sacred place.

Schéissendëmpel Falls, perhaps the most famous stop on the Mullerthal. It’s easy to see that this is the part of the world where western fairy tales originated… Hansel and Gretel, Snow White, Little Red Riding Hood… I feel like they’re just around the bend and if I keep walking, I’ll catch up with them.

The Mullerthal Trail has several sections that go through narrow rock crevices. The first one is not too long, but the second one is about 50m long and has one section where you have to turn sideways to fit. Someone wearing a regular sized backpack would not be able to get through.

I save my most extreme claustrophobia for places that are low, but narrow and long is high up there, too, so this was no small thing for me to accomplish. There was an option to go around, but this was one of the challenges on this walk that I wanted to face. And I did.

Didn’t meet up with any these, but I still wish I knew what they are.

The traditional end point of the Mullerthal is the storybook village of Echternach.

I’m not sure why I saved this piece of family history for the second to last day, or why I felt I had to get up at 6:30 a.m. and walk a grueling and challenging trail for six hours in the middle of a heat wave to arrive here, but that’s how it went down.

Echternach is where my parents got married — and without quite realizing it, I deliberately saved it until almost last. As such, the day’s walk reminded me very much of the last day into Santiago, walking towards a great cathedral, seeing the spire from the hill a few kilometers away, walking dusty and sweaty and tired into the city to the cathedral steps.

Luxembourg has been a metaphorical and personal pilgrimage all along, of course, to reclaim my heritage, but that day, for a day, it became a literal one, too.

The Basilica at Echternach, where my parents were married.

I stood on the steps in front of the door, where the only wedding photo of my parents I’ve ever seen was taken, and tried to imagine how my mother felt, standing there looking out over the grand square.

Now is as good a time as we’re going to have, then, to share the last bit of my story. Or rather, my mother’s, because the reason she was standing on those steps as a young bride newly married to an American is both complicated and mysterious. It’s one of the secrets that defined both my childhood and our relationship and probably our ultimate estrangement.

After my mother’s family squandered their fortune when she was 16, my grandmother became a shopkeeper and my grandfather continued to work as a carpenter (though as I understanding it, drinking, gambling and womanizing continued to be his primary vocations). My mother took going from wealthy society girl to middle class shopkeeper’s daughter pretty hard. That much I know.

At 18, she moved to Paris. That much I know, too. And that’s where the mystery begins, because she always refused to talk about her years there. She also swore she would never return to Europe and never would say why.

My mother met my father at a party at the military base where he was stationed — she was the date of an American military officer and my dad always said he felt like Grace Kelly had just walked in the room. He got up the nerve to ask her to dance, and she said, “I can’t, it wouldn’t be proper.” But he persisted and won the hand of his lady.

I’ve often thought of this story, and my mother’s silence about her years in Paris and her refusal to go to Europe and her fall from her wealthy lifestyle, and wondered.

I have a theory that she lived the life of the Audrey Hepburn character in “Breakfast at Tiffany’s” while she was in Paris — not quite a “girl for hire,” but not NOT one, either. She was beautiful and elegant and schooled in all the social graces and in need of money… an attractive escort for wealthy men in Paris… but without a fortune, not suitable as a wife. I wonder if she was at that party that night with a client, not a date. And I wonder if my father didn’t realize that (and never did), because he didn’t run in those circles and he loved her so much that he was blind to her dubious past.

My mother once told me she married my father as a way to get out of Europe — that and her refusal to return might point to not wanting my father to learn the truth about her life when she met him.

A friend of mine who was a former covert CIA agent pointed out that during the Cold War years, the CIA and other western intelligence services recruited young, attractive upper class women as agents to date subjects under surveillance and report back on their “pillow talk.” He pointed out that that my mother would have been a prime candidate, given her background, her need for a discreet source of income and her love for all things American. That would explain her presence as the date of an American officer, and also her stony silence about those years.

Either or both are plausible. Either or both would have made for interesting thoughts as she stood there, a new bride — a spy? a former semi-prostitute? — married to a poor working class man she didn’t love, hoping for a new life in America.

And it would explain a bit about why she wasn’t thrilled with the life that awaited her — the wife of a Texas farm boy stuck in the dry Southwestern desert, living in a trailer on food stamps. Hardly her American dream. And why she clawed her way into college, graduating with more than a 4.0 — class valedictorian and the first in her family to do so.

And it would explain why she was never that keen on motherhood — just one more thing trapping her in a life far from the one she was born to live, far from the one she dreamed of when she married my father.

I think the young bride standiing on these steps so many years ago had a broken heart and I think that heart never quite healed, no matter how much she tried to soothe the pain with 12 year old Scotch and silence.

And knowing all too well what it feels like to be trapped, or at least to feel you are, I thought that perhaps the kindest thing an unwanted daughter can do for a mother is to release her from that role. To let her go.

The basilica in Echternach was partially destroyed during WWIII, so a lot of it was rebuilt after the war. But UNDERNEATH the cathedral is still the original construction from the 11th century (1016, I think).

There is a chapel dedicated to Mary below the cathedral itself that felt very much like a pagan goddess temple, particularly nestled in the earth with the softly curved walls. An appropriate place to light a candle and offer a whispered prayer for that young bride and her Texas farm boy husband.

On the way back, I stopped to buy a postcard of the cathedral, and sat at a cafe and scribbled a short message saying that I’m okay — my first communication with my parents for over a decade. I added their address, which I still knew by heart, and slipped it into the mailbox before I could change my mind. It had no return address. I don’t know if they’re are even still alive, but if they are, it was likely be the final communication between us in this lifetime.

After the emotional intensity of Echternach, I sought refuge for the final few nights in a tiny “cave house” in Hollenfels, where Christiane (also my mother’s name) welcomed me with a bottle of homemade cider. Her fur family — consisting of a horse, a dog named Soleil, a house duck and a couple of llamas — provided the much-needed peace and solace that being around animals always does.

Cave House became my refuge and sacred space in Luxembourg. At sunset on the last day, I walked to the end of my favorite trail and left an offering. White swan feathers for peace, a tiny pine cone from Oregon that somehow hitched a ride for possibility, an apple to symbolize fruitfulness and some bread for the forest creatures.

If this were a movie, this is the point where I would ask the owners, “Can I stay?” And then I would get a part time job waitressing at the little cafe across the street and write and befriend the alpacas. But I had my own fur family and future waiting for me elsewhere, and part of traveling is learning how to say goodbye. Reluctantly. Very reluctantly.

Blessed be, land of my birth and of my heart. Thank you for your gifts.