My first journey of self-discovery was spending a year in a yurt high up in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains of northern New Mexico. My instinct was insistent that I had to go, but I had no real idea of what I was doing and I would arguably bungle this particular journey in every possible way when it came to self-discovery. But it was here that I first realized the power of such an experience to put me in touch with long-buried parts of myself and to help me to find the clarity and courage to make major life changes.

Arrival. Dojo and Marley were city dogs who’d never experienced the freedom of having literally thousands of acres of woods to explore without fear of cars or leash laws. It had been years since I’d had that kind of freedom, either.

The view of the yurt from afar. On the first day, we got lost exploring the woods and made it back just before nightfall, but as time went by, every tree and arroyo began to be familiar, like old friends and then even more intimately, as extensions of myself.

The interior. There was a woodstove for heat, a simple kitchen, a bathroom with an incinerating toilet and a sink and shower and an outbuilding with a washer/dryer. In the winter, the pipes froze, so the washer/dryer didn’t work. The incinerating toilet stopped working about three months into our stay despite multiple attempts to fix it with mail ordered parts, so it was the woods from then on. Dial-up internet was the only connection available, through a basic phone line that worked only when the mice didn’t chew the cable. It was simple, inexpensive, and most of all, had the things that I most craved in abundance: silence, solitude and a night that was truly dark.

A few minutes from the yurt was a hidden, private lake — something the owner had failed to mention because a several year long drought had dried it up. The drought broke almost literally the day we arrived, and we enjoyed the lake for most of the year, though it froze over in the winter when the snows came.

The day we found the lake — quite by accident — was the realization of a fantasy I’d had since childhood to find a secret place close to home that I didn’t know was there, like Lucy’s Narnia or Alice’s Wonderland. I christened it Lake Francis, after the patron saint of both animals and the city of Santa Fe.

Being a lab, Marley was in heaven with her own lake to fetch balls in anytime she wanted.

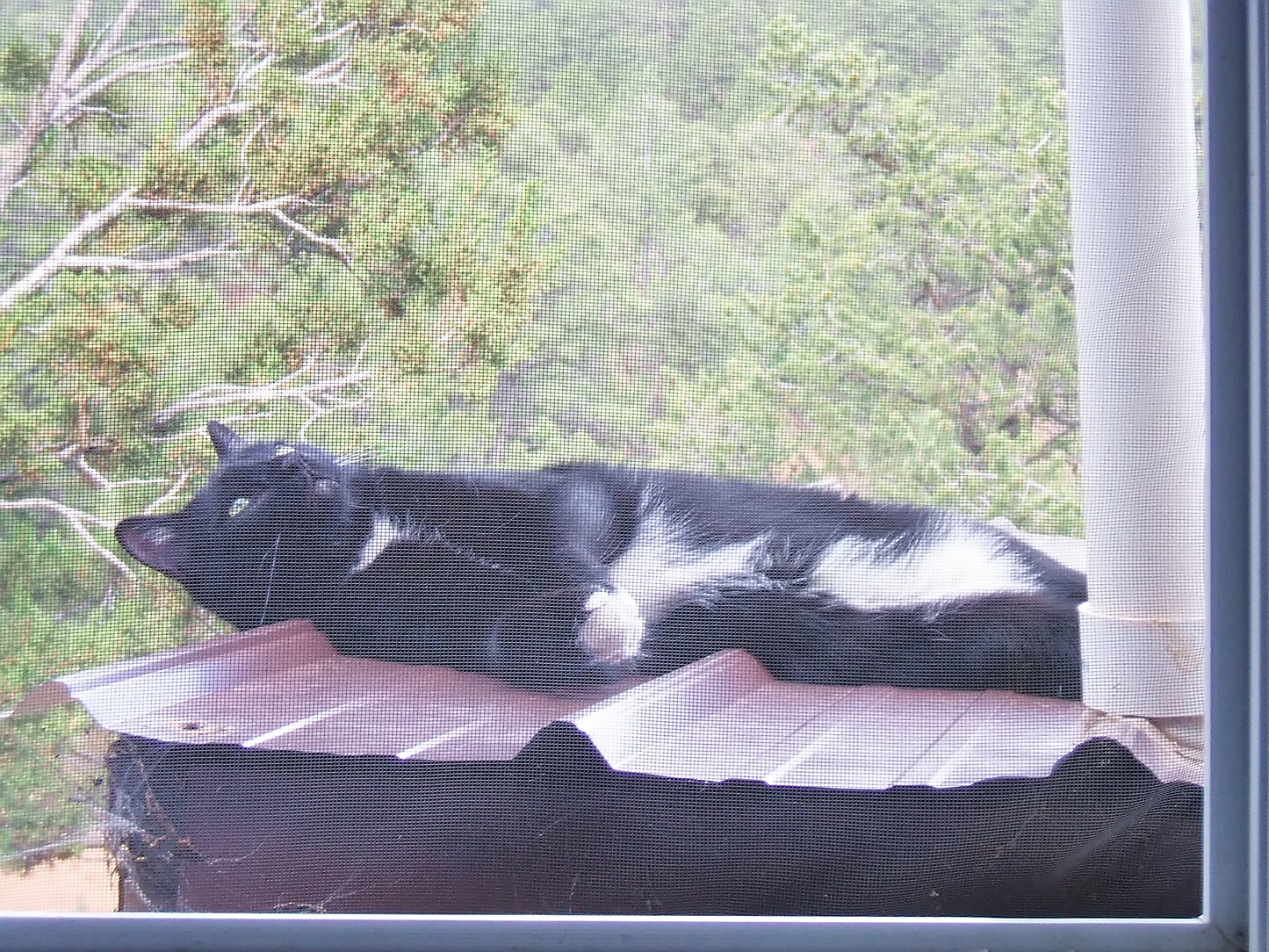

Moe the Cat came with us as well. An indoor cat in LA, he was so desperate to get out to explore the woods that he literally threw himself against the door, crying, until I gave in. He had a summer of freedom, till one late fall day, he failed to return home. We were all devastated, especially Dojo Dog, who was Moe’s best friend.

Everyone told me that there was no way a “city cat” could survive, but I knew Moe better than that and refused to give up on him. After a month of searching the backwoods for him, I found him in a neighbor’s barn, fatter and happier than when I’d last seen him. He’d survived thrived through snowstorms, coyotes, owls and who knows what else. After that, he still went out, but only on supervised excursions, joining the dogs and me for hikes and returning with us to the yurt.

I was just learning about photography that summer, an avocation that would result in three solo gallery shows in Santa Fe and San Francisco, before I realized that being a gallery artist was not my path. Since I was my only available subject, I did a lot of self-portraits. This is my favorite, with the blue guitar that I’d brought along. I finally learned to play that summer as well, and spent many afternoons strumming and singing old Emmylou Harris songs while the dogs and Moe played in the woods.

That first summer was as close to perfect as anything has ever been in my life. I had my beloved animals, plenty of money with no need to work, no obligations and the freedom to go where I choose, when I chose. No email, no phone calls, no snail mail, no schedule. I didn’t even have a clock and often didn’t know (or care) what time of day or day of the week it was.

When the drought broke, it really broke. Summer is monsoon season in New Mexico — every afternoon, the sky opens and dumps buckets, and that season was particularly wet. I went into town one day on a bare, dry, flat road, and came back to a river. I’d grown up in New Mexico, but I’d forgotten how dangerous flash floods could be. I tried to drive through it, reasoning that it wasn’t that deep, even though there were logs the size of my car being carried in the current. I made it about 100 feet before the car stalled and began to fill with water. I had to risk getting to the “shore” and shot this photo as I was escaping. Fortunately, the dogs weren’t with me at the time.

Getting rescued… sigh. I felt like — and in truth was — the foolish lady from California who drove into a flood (it didn’t help that the car had California plates). I felt a little better when the guys told me I was only one of many cars they pulled out that afternoon and I think they enjoyed being heroes for a day.

It’s the lingering storm clouds after the daily “monsoon” that create the sunsets the Southwest is famous for. There is nothing like them anywhere else I’ve ever been.

For the first few weeks, I photographed every sunset, until I realized that the world did not really need more sunset photos — but the world much needs more people who are able to stop what they’re doing and simply watch and appreciate the sunset. So that’s what I did from then on. I rarely missed one while we were in New Mexico — whatever was happening, it was set aside when the sun began to go down, a habit I still try to practice to this day whenever I am.

Hiking one day, we came upon a hidden valley, which I unimaginatively named Hidden Valley. 🙂 It’s the most peaceful place I’ve ever been, and to this day it’s the place I go when a guided meditation asks me to “picture a peaceful place.”

Dojo and Marley playing in our Hidden Valley. I had never seen them so happy, and was so grateful to have been able to give them the experience of living the way nature intended for dogs to live.

About two miles past our Hidden Valley was an abandoned, partially-constructed house. I was enchanted with the idea of living deep in the woods and flirted with the idea of buying it and finishing it — I even went to the county assessor’s office to look up the owner and tax info on it. The house is so remote that it would have required an ATV to get to, or a snowmobile in the winter, and it would have had to be completely off-grid. I ultimately abandoned the idea as it was too much to take on at that point in my life, but I still think about that house every now and then and wonder if it’s still waiting in the woods for someone to finish it.

The heavy rains that broke the drought brought to life all the seeds that had been dormant in the ground for years (a metaphor for that whole summer’s effect on my psyche). As a result, fields of yellow flowers covered acres as far as the eye could see. All my life, I’d had daydreams about wandering through a field of wildflowers in a lovely dress with a straw hat. I’d been wearing both on a regular basis, so when the yellow flowers bloomed, I took the opportunity to make that dream come true.

The view at night from my door.

Aspens in the fall. I learned that an aspen grove is a single organism, with every tree connected to every other tree below ground.

Harvesting pinon nuts. Different from pine nuts and unique to the high mountains of the Southwest, they’ve been a favorite of mine since childhood and are mostly unavailable outside of New Mexico as they resist commercial growing and harvesting. Pinon trees generally yield a crop only every eight years or so — in another remarkable feat of good timing, there was a bumper crop that fall and I had acres and acres of trees from which to harvest all I wanted.

Rainbow over the mountains. A frequent sight.

The first week of September is the Burning of Zozobra in Santa Fe. Attended by over 50,000 people, Zozobra is the burning of a 50-foot tall effigy. The actual burning is preceded by a day-long ritual in which the citizens of Santa Fe fill Zozobra with things they want to let go of — letters, results of medical tests, old wedding dresses, photographs (the flammable stuffing of Zozobra is made up of old shredded court records donated by the city). The mayor then sentences Zozobra to burn “for the sins of the community.” The Fire Priestess begs for Zozobra’s life in a ritual dance, but the crowd, chanting “burn him, burn him!” refuses, and the effigy is lit with TNT and fireworks. The burning is followed by a week of fiesta to celebrate a new beginning. Zozobra is a deeply pagan ritual of catharsis that predates Burning Man by over 60 years, the first Zozobra having been in 1924.

I was fortunate to be the official photographer for two years, which meant I had literally the best seat in the house.

Another shot of Zozobra in full-burn. Afterwards, when the crowd disperses, the crew and firefighters roast marshmallows over his smoldering corpse.

Coming back from a hiking day trip, the dogs and I found a raccoon that had been killed by a car. Someone had already taken the tail, but I couldn’t bear the waste of such a beautiful creature and wanted to find a way to honor its life rather than leaving it by the side of the road. So I had the idea that I’d take it home and at least save the pelt. (Read about how that turned out.)

I managed to skin it — something I never thought I could do or even imagined doing before this — but drying/curing an animal pelt turns out to be much, much harder than it sounds and all the advice I found online was contradictory. I ended up sacrificing the hide to the coyotes, which probably would have been the result anyway had I not intervened. But I’m grateful for the experience.

I had only intended to stay for a couple of months, but was offered the opportunity to stay for a full year. I said yes, wanting to experience the full cycle of the seasons, including the winter, in this remote location. What I hadn’t counted on was not having adequately prepared by stocking firewood through the late summer and fall the way the locals knew to do.

By the time I started cutting, the dead pinon trees that would have been easy to cut in the fall were frozen rock-hard and most of every day was spent cutting enough wood to last me till the morning. I only had an ax, because I didn’t yet trust myself to operate a heavy chain saw, and because I couldn’t quite bear to break the silence of the woods with a motor.

I set myself the challenge of keeping myself and the animals warm for an entire winter using only wood I cut myself with my ax. I was able to do it, but for all its charm, the yurt was poorly constructed and not well insulated, and there were many times when I wasn’t able to cut enough wood to last the night, or what I cut was too wet to burn. Those nights, I went to bed early, as soon as the wood ran out, wearing every piece of clothing I owned and still freezing, huddling with the dogs and Moe under every blanket I had to keep warm. I did not know what cold was until that winter, and every time I am somewhere now where central heating is available with the flick of a switch, I think of the thousands of years that humans had to rely on their ability to cut firewood to stay warm. I will never again take being warm for granted.

I grew to love cutting firewood, but not that winter, when the wood was frozen and I was cold almost all the time. The next season, I’d buy a chainsaw and start cutting in August, and I have seldom enjoyed anything as much as I did filling every spare corner of the yurt with firewood. But that pleasure was a long way off still, that first winter.

The very first tree I ever cut. (It was dead — I would never cut a living tree.) It took me days to cut it, and then more days to split the wood into burnable pieces once the actual tree was felled.

The first snow. I’d spent the past decade in Southern California and being able to spend a winter in the snow was one of the reasons I stayed for the year. I got what I wanted and more — record snowfall that year.

Marley and Dojo loved the snow as much as I did. Moe the Cat was less pleased, and elected to stay indoors until the ground was clear again.

The view from my kitchen window. We had all the way to the mountain in the distance, miles away, and beyond to roam, mostly in solitude.

Marley Dog. Rescued from a puppy mill with a congenital heart condition, she was having a life of joy and freedom and I was so glad to be able to give her that after what she’d been through. She died too early, at ten years old, but she had more adventures in her short life than most people do.

A snow-covered tree at Lake Francis, which was frozen over for the winter.

Christmas. I had hoped to spend the holiday with my then-beloved, but that didn’t happen. I was faced with my first-ever Christmas alone, which was incredibly painful — all the more because Christmas in Santa Fe is particularly community-oriented. One of the few places that resists commercialization of the season (the small mall is virtually deserted on Christmas Eve), the community celebrates by gathering in the town square and sharing cider and small bonfires lit in the street, followed by Midnight Mass at the cathedral. It is a deeply moving and spiritual experience, but I had difficulty appreciating it on my own that year.

Another photo of Christmas in Santa Fe — one of many bonfires lit along the side of the road where anyone is welcome to stop and warm themselves.

Blizzard, New Year’s Eve. The snow was over the dogs’ head and even if I’d had a 4-wheel drive, there was no way off the mountain for several weeks. As beautiful as it was, I sunk into a deep depression as the Christmas alone, as well as the extreme isolation of being snowbound, forced me to deal with the demons rattling around in my head that I’d left Los Angeles to get away from. But, of course, “wherever you go, there you are” and the demons were right there waiting for me when I stood still long enough for them to catch up.

Not to mention that the deep snow meant no cutting firewood, so I was cold. Very cold.

The dogs had fun playing in the snow, and I used them as canine snowplows, throwing the tennis ball where I wanted to walk and letting them cut a trail for me. They came back inside with ice balls all over their paws and coat, which I had to defrost for them.

Dojo’s tail, cutting a path through the snow as he searched for a tennis ball. When the snow finally melted, we found dozens of soggy tennis balls…

Carelessly, I hadn’t paid attention to the weather report before the blizzard hit, so while everyone else was stocking up on food and supplies at the grocery store, I… wasn’t. When the storm came, I had few supplies and literally used every scrap of food in the house to keep the dogs, Moe and me fed. I could have called for help, of course, but I didn’t want to be the stupid lady from California who forgot to buy food so I was determined to make it till I could get back down the hill.

When I was able to cut a trail to get as far as the front gate, I discovered a package left there by UPS before the blizzard hit. I opened it up to find a holiday box of See’s Chocolates addressed to a prior occupant. Fingers trembling with cold and eagerness, I tore open the box and nearly broke my teeth on the frozen-solid candy. I took it inside, thawed it in front of the fire, and feasted on the whole box. It was the sweetest chocolate I’ve ever tasted, or likely ever will.

After a severe winter, the thaw and the first flower of spring. I love snow, but I was surprised at the depth of my joy at seeing the bare ground again. It was a gratitude that felt primal in its intensity, and I imagined that was how ancient people felt when the days grew longer and the earth came to life again.

By now, I had walked the land so much that I felt like there was no separation between it and my own body and after a winter of struggles with depression and extreme solitude, I felt myself coming back to life again along with the land.

Moe the Cat was happy for the spring thaw, so he could resume his (supervised) explorations.

My friend Ann walking the labyrinth in Santa Fe. Her friendship helped a great deal in coping with the isolation during that year. Years later, she would visit me in Southern California and walk the labyrinth in Topanga Canyon.

Spring brought the Pilgrimage to Chimayo, an Easter ritual in which Catholics walk, often for several days, from their homes to the Sanctuario de Chimayo, an ancient church akin to Lourdes. The ground at Chimayo is reputed to have healing powers, and people come from all over the world to be healed of their afflictions, leaving rosaries, crutches and other tokens in appreciation and devotion.

Crutches from those who claim to have been healed at the Sanctuario de Chimayo.

Vaqueros (Hispanic cowboys) with their horses at the stone crosses at Chimayo. Many people choose to do the pilgrimage on horseback.

Cross and offerings inside the Sanctuario de Chimayo. Unlike the Camino de Santiago, which has become a pilgrimage for people of all faiths and no faith, the Chimayo pilgrimage is still largely a Catholic tradition. Though I didn’t walk to Chimayo, witnessing the pilgrims walking along the side of the road that spring formed the inspiration for my pilgrimage on the Camino de Santiago many years later.

As spring became summer, the pear cactus flowers bloomed. I’ve come to see this photo as representative of my time in the yurt — the blooming of a new flower from the prickly spines of an old life. Though it would take me many more years to get myself free of the demons I brought on the trip with me, that year was the beginning of a life long exploration of the transformative power of journeys of self discovery like this one that continues to this day.