A well-lived life in one’s 20s often means actively seeking out new places. But a well-lived life in one’s 40s may mean learning to hold still.

It’s a Sunday afternoon and I’m sitting on the patio admiring the fledgling garden I just planted. The temperature is perfect for a spring day, and I can hear the fountain bubbling in the background. River the Dog and Moe the Cat are snoozing side-by-side in a patch of sunlight with the bone-deep peace that only safe, happy and well-loved animals seem to have. A passing breeze brings the scent of the jasmine that’s blooming nearby.

I am, I realize, content. This place feels… right. Not perfect — lord knows not perfect — but, geographically-speaking… right.

This is a big problem for me, because that contentment feels oh so very wrong. Not a moment after the contentment comes the impulse, by now familiar — the almost irresistible urge to pack everything up and move somewhere else. Anywhere else as long as I haven’t been there before. Immediately.

I’m not surprised at all by this sudden urge towards flight. It’s the inevitable emergence of my lifelong geographic commitment phobia — the reluctance to declare after a lifetime of arrivals, tryouts and departures for greener pastures, “This is it. This is my place. This is Home.”

Over the past 30 years, I’ve lived in some beautiful places. Places that people who live in other, less beautiful places visit while on vacation and dream about moving to. Santa Fe, Boulder Colorado, Nashville, the Pacific Northwest, to name just a few. And now Topanga Canyon outside of Los Angeles, nestled in the mountains just minutes from the beach, and easily one of the most beautiful areas of one of the most cosmopolitan cities in the world.

With each new place comes the thrill of love infatuation — the newness, the discovery, the intoxicating possibilities of the unfamiliar. The opportunity to reinvent myself and my life on the pristine canvas of new geography. I get goosebumps of delight just thinking about it. And with change of venue comes the certainty that this place, this new place, is going to be the One that will hold my attention and affection forever.

But as usually happens with infatuation, eventually the charms wear off, the imperfections begin to show, and I decide that the current man place isn’t the forever man place after all.

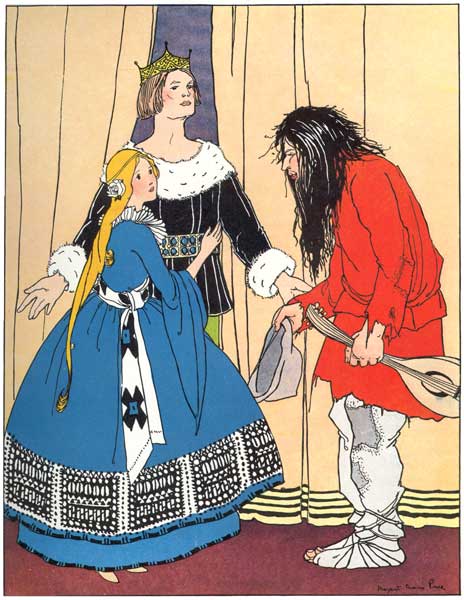

I remind myself more than a little of the archetypal fairy tale princess who rejects every suitor in the kingdom, declaring none of them to be quite right for her, no matter how handsome or noble or kind. In the fairytale, of course, the princess invariably runs out of options and ends up married against her will to a passing beggar — the only man in the kingdom whom she hasn’t rejected, but who ultimately turns out to be a prince in disguise, sent to teach her the life lessons in gratitude and humility required to truly be a princess in spirit as well as in name.

When it comes to geography, I’m past due for the beggar. And this feeling of contentment I have is coupled with the fear that he may have finally arrived at my door.

I consider all of this as I contemplate my newly planted garden. I’ve lived here for four years, and this is the first year I’ve planted a garden, even though I’ve wanted one since I moved in. Every time I considered planting one, the little voice in my head would caution me not to because I wasn’t going to be here that long. Why invest money and time in nurturing plants that wouldn’t bloom or ripen until long after I’d moved on.

If my current urge to move on were like the ones that came before, I wouldn’t be as unsettled by the feeling as I am. Dysfunctional or not, my serially monogamous relationship with place is a familiar pattern, and as humans, we’re more or less hard wired to prefer the dysfunction we know over the adaptation we don’t.

But this time feels different, and that’s catching me more than a little off guard. Because instead of starting strong and fading, as infatuation tends to, this feeling of being home comes four years after I moved here, right when I’d normally be falling out of love. It’s a sense of comfort that comes, I suppose, with growing more deeply in love with someone despite their flaws, rather than falling in (and out of) love because they’re not perfect like you hoped they’d be. And I am not ready or prepared for that kind of geographical love, particularly not with a place as imperfect as this one.

My list of reasons for rejecting Topanga Canyon as a permanent home is definitive. Like many people searching for true love, I have a List. For a man, it might read, “No smokers, no drummers, absolutely must love animals and Buffy the Vampire Slayer.” For a place, it reads similarly, and includes, “Must Have Snow and Seasons. Must Not Get Too Hot, Must Not Have Crazy Inflated Real Estate Prices.” And so on.

It does not, of course, snow in Topanga Canyon, and there are no seasons to speak of. One day is exactly like the next — minus the few months of the year when it’s so hot that even in the canyon, it’s hard to breathe without suffocating. And don’t even get me started on the price of real estate.

These are, at least to my mind, legitimate concerns. After all, climate is a pretty big factor when it come to lifestyle, and real estate prices have a major impact on financial freedom and long-term options. But in the back of mind, there’s a persistent voice that also calls bullsh*t. The princess isn’t rejecting suitors because none of them are good enough. She’s rejecting suitors because of what she fears would happen if she finally said yes to one of them.

At the root of my geographic commitment phobia is the fear that if I stop thinking of everywhere I live as temporary, if I stop putting everything else on hold while I search for the perfect place and instead, decide to Be Somewhere, I will have to — finally — do the two things I really, really don’t want to do.

Connect and commit.

Choosing a forever place — or at least a long-term place — means doing the hard and often messy work of becoming part of a community, creating a network of relationships, making commitments to professional, civic and personal ties that won’t conveniently evaporate when I decide to move on. Things that a lifelong introvert like me tends to see as roughly equivalent to being trapped in an endless and particularly horrific episode of “Worst Case Scenario.”

Knowing that wherever I live is temporary has thus far almost completely relieved me of the obligation to truly work on relationships (getting attached just makes it harder to say goodbye, no point in it), focus on a career path (writers can work from anywhere, I rationalize, which is only partly true), and make grown-up financial plans (no point in buying a home if I’m moving on in a year), to name a few.

I am not comfortable with being comfortable. The familiar doesn’t tend to soothe me and the predictable fills me with dread most people reserve for the specter of being buried alive — which is exactly what committing to staying in one place forever feels like to me. Underlying the security that comes with the known is the sickening fear that if I commit to this place and situation, my life is over. No more possibilities, no more adventures or do overs or “better than’s”. I’ll have to stand still and learn to be who I am, and I do not feel ready for that.

This existential dread is, I think, hereditary. Or perhaps more accurately, reactionary.

My mother spent her life as a teacher in a small town in the middle of nowhere because she was afraid to reach for anything more, and she made it clear to me that not only was her predictable and very small life a psychic death for her, but that as her only child, I was solely responsible for consigning her to the tedium and predictability of that life. My father gave up his creative dreams so he could give my mother the life she didn’t want so she could raise a family she didn’t want.

My fear of geographical commitment is, I realize, a reaction to this quiet family tragedy. Equal parts rebellion against my parents’ claustrophobic lifestyle and a desire not to repeat their mistakes by refusing to settle either literally or metaphorically for what is at the expense of what could be.

It takes courage, I’ve always been told and have always told myself, to pick up and move to a new place where I don’t know anyone, to start over again from scratch. And my refusal to put down roots has rewarded me with a life of adventure and variety of experience that most people will never have.

But like the princess who refuses the challenge of connection, I also recognize the element of cowardice at work here. Freedom, as the song goes, is just another word for nothing left to lose.

A well-lived life in one’s 20s often means actively seeking out new places. But I suspect that a well-lived life in one’s 40s may require learning to hold still long enough to build the things that hold the meaning and substance of a life– a home, a career, a family if one’s inclined in that direction, a circle of connection and relationship that goes beyond the transitory, and to give these things the opportunity to grow like the vegetables and herbs — perennials, not annuals.

In one’s 40s, the greater act of courage may be to face the fear of what might happen if I stand still long enough to experience more than just the beginnings and endings of things and to be willing to deal with the messy middles, where I suspect most of the actual living of life happens.

Still, I wish there was more to go on here. Some clue, some sign that this place was The Place, that this is the right choice and worth the sacrifice of what might be Elsewhere. But of course, that’s not how the story goes.

The princess is forced into marrying the beggar, and his true identity as a prince is hidden from her until she lets go of her fear and allows herself to love the beggar for who he is rather than for what she wishes he could be.

Sitting here under the trees, wrestling with the demon of commitment and the siren call of new places, my finger hovering over the “reset” button, the lesson is not lost on me. The blessings of a full life are likely available to me only once I let go of the fear of staying still long enough to see my garden bloom. Until then, they’re hidden behind a pile of moving boxes and “I’d love to but I won’t be here that long”s.

But oh my lord, I really don’t know if I can live without snow.